Flight 93 National Memorial: Where America Remembers

On September 11, 2001, terrorists affiliated with al Qaeda hijacked

four planes. Two struck the towers of the World Trade Center in New

York, one at 8:46 a.m. (American Airlines Flight 11) and the second at

9:03 a.m. (United Airlines Flight 175). At 9:37 a.m., a third plane,

American Airlines Flight 77, crashes into the Pentagon. Thirty minutes

later, United Airlines Flight 93 crashes into a field in Somerset

County, Pennsylvania, after passengers unsuccessfully attempted to take

control of the plane from the hijackers. It is supposed that Flight

93’s ultimately destination was the U.S. Capitol building in Washington,

D.C.

Flight 93 National Memorial, near Shanksville, Pennsylvania,

commemorates the heroic efforts of passengers and crew members to stop

the hijacking. Administered by the National Park Service, it is the

only federal property that "remembers" what happened that fateful day.

I

have visited over two dozen national parks (most of them historic

properties), and I worked at one as a seasonal ranger for three

summers. By far, this was the most moving experience I have ever had at

a national park. It’s one thing to go to the Assembly Room at

Independence Hall and see where our nation was founded. It’s something

entirely different to visit a place where our nation’s freedom was

defended by ordinary people who didn’t want hijackers to attack our

nation.

Flight 93 is distinctive among the four hijacked flights

that day because it’s the only one that did not reach its intended

target. The flight’s departure from Newark was delayed because of

normal early morning traffic at the airport, which means that its

passengers knew about the attacks on the World Trade Center when

terrorists took control of the plane at 9:28 a.m. The passengers

formulated a plan to retake control of the cockpit from the hijackers;

ultimately, the hijackers chose to crash the plane rather than let the

crew and passengers regain control of the aircraft.

The

aircraft exploded upon impact, releasing over 7,000 gallons of fuel in a

fireball that rose higher than the hemlock trees surrounding the area.

Debris scattered over the field. Today, the walkway from the Memorial

Plaza to the Memorial Wall is lined with black concrete, black because

of the coal in the region. The black wall also separates the debris

field from the walkway; in other words, it provides a barrier between

tourists and where the human remains rest.

Park

visitors occasionally leave tributes in the small niches in the wall

and at the Wall of Names. Visitors also have an opportunity to leave

expressions of gratitude at the Memorial Plaza.

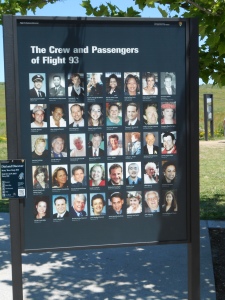

The

Wall of Names follows the flight path of Flight 93 toward the crash

site. It identifies crew members with their position (flight

attendants, etc.), along with naming the passengers who were not

involved in hijacking the plane (there were 44 people on board that

flight, but only 40 names are included on the Wall of Names). One thing

that struck me when I visited the Wall of Names was how somber it was.

Typically, at a national park, you hear people talking and

laughing–not at Flight 93 National Memorial. Park visitors truly

respect what happened at this site, and they treat it with proper

reverence.

At the site, several wayside signs provide information on the flight and what happened that fateful day.

One

thing is obvious when visiting the site–it is designed to honor those

heroes who prevented the hijackers from achieving their goal. It does

not memorialize the hijackers by name on the Wall of Honor, not does it

include their photos on the sign identifying the crew and passengers of

the flight. Some might consider that to be sanitizing the history of

the events, but since the park is a memorial to those who prevented the

attack on the U.S. Capitol (especially since Congress was in session

that morning), then I support their interpretive focus.

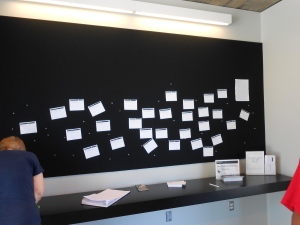

Flight 93

National Memorial is in the process of building a Visitor Center that

will include a Learning Center, and it is scheduled to be completed in

late 2015. If you travel there before its completion, you can view the

progress of construction from the Memorial Plaza. In any case, it is

definitely worth the trip to visit this national park–and you are

encouraged to leave a note expressing your gratitude for those who gave

their lives that day or just write your thoughts about the site.